Northern Michigan has many examples of well-designed towns and villages, mostly built during the late 1800s. But it has been generations since new neighbors reflecting that classic design have been built there.

“Modern” zoning laws that separate homes and stores from jobs have made new town centers and neighborhoods virtually illegal. So most local officials, developers, and bankers are familiar only with spread-out, auto-focused suburban development. As northern Michigan grows, we must make it easy to again build quality town centers that, as so many area residents clearly desire, preserve rural character.

This section of Going to Town offers guidance to officials, developers, financiers, and citizens on how to build new town centers and neighborhoods or grow old ones.

Three key elements to consider are planning, design, and execution.

Element One: Right scale, right spot

All such projects should be compatible with the community’s master plan. Because zoned communities must update their master plans every five years, citizens have opportunities to review projected growth patterns. When a project is proposed, communities must carefully determine whether it fits that plan and what its scale and density should be. Local planning officials must determine what additional infrastructure is required for the project and how much capital it will take for those improvements, including roads, sewers, water, parks, schools, and public safety. These steps give the community an excellent idea of what opportunities there actually are for New Urbanist development, which comes in three varieties:

The first expands existing villages and towns by adding new neighborhoods. Extending an existing street grid and mixing in appropriate commercial development can grow a village without incurring large infrastructure costs. The New Neighborhood in Empire is an example.

The second, called “infill” development, applies to already-developed urban areas—including brownfields, abandoned properties, or parking lots. River’s Edge and Midtown in Traverse City are examples.

The third involves building a brand-new town center where there’s little or no existing development. This more unusual approach occurs in townships that have no commercial center but are facing significant, diffuse growth. An example is Acme Township’s vision for a town center on an undeveloped, 172-acre field. (See box, page 17.)

Thorough research and planning are essential. Review regional and local growth trends and market studies to ensure the project’s commercial and residential components make sense. Consider how master plans of neighboring communities could affect the market. County planning staff can help assess demand for future growth.

The process should also include a community “build-out analysis,” which determines how many new structures current zoning ordinances ultimately allow. The analysis is a good starting point for communitywide discussions about future growth and usually indicates that if current zoning remains unchanged, the area will eventually be filled with low-density residential development.

One solution that leaves future population projects unchanged but preserves open land is a “transfer of development rights” program. It allows landowners living in rural areas that a community wants to protect to sell their development rights, which are then transferred to a designated area zoned for higher-density development, like a town center or new neighborhood. These transfers require extensive community planning in the designated areas, but require no public funds. TDR programs allow rural communities to protect their open space by growing their village centers.

| |  |

| | MLUI/Gary Howe |

| | Because houses in Empire and The New Neighborhood are close together, installing a new water system is relatively inexpensive. |

Include the public in every step. Good master planning is transparent and includes all key stakeholders, especially those who could derail a policy with their opposition. Invite the participation of community stakeholders, including owners of vacant land, existing residents and business owners, realtors, developers, and neighboring government officials.

Officials should post drafts of proposed policies and project maps in newspapers and prominent buildings, mail them directly to residents, speak about the process at local service clubs, survey residents, and host neighborly meetings, complete with food and entertainment, to gather public input.

Element Two: Good Design

While there are many designers who can help lay out a new project, they will mostly follow the same basic set of New Urbanist principles.

Street grid design and placement require particular care. An interconnected street grid moves more traffic more efficiently than suburban cul-de-sacs that dump onto main roads; alleys allow garages and vehicles to be placed in backyards. Narrow, tree-lined streets and parallel parking calm traffic, while nearby transit stops encourage more pedestrian and commercial activity and increase convenience.

It is also important that public spaces the grid establishes are surrounded by buildings that face toward them, for increased public safety. All grids should work around, not pave over, natural features such as wetlands or steep hills. Orienting the grid to emphasize landmarks increases everyone’s sense of direction and place.

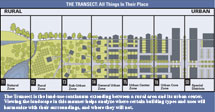

Traditional neighborhoods and mixed-use form the basic design unit. They are typically no more than a quarter-mile across and require about five minutes to walk from the edge to their commercial center. That is essential; residents want to make far fewer daily car trips.

The design must carefully consider the size, placement, and aesthetic quality of buildings in order to create a continuum, not a mad jumble, which facilitates a wider range of possible activities. For example, placing a post office next to a convenience store next to a condominium project can be attractive if the look and scale of the buildings are correct. The resulting mix that such design enables increases a project’s walkability and economic stability.

Many elements can and should be mixed together. They include commercial and office space that provide jobs and boost pedestrian traffic, plus residential units—including both upscale and more affordable single-family homes, condos, and apartments—that encourage diversity of people and design.

Retail establishments should serve nearby residents’ needs, but can rub elbows with national chains. Light industry and institutions (hospitals, schools, even jails) can fit well in residential areas, too, if properly designed, again adding to pedestrian and auto traffic. And every quality community must offer parks and recreational spaces; without them, a community simply will not attract new residents.

Use “Smart Codes” to build community character and make mixed-use work. Much of a neighborhood’s feel stems from what the buildings look like and how they command the space around them. But traditional zoning ordinances say nothing about these crucial elements, often referred to as form; instead, they focus almost entirely on use.

In recent years, however, “form-based codes” have become powerful tools that regulate form and generally do not regulate use. They remove the chief reason people dislike living in commercial districts—buildings and roads cast in uncoordinated, unwalkable jumbles that only make sense to someone driving a car.

Form-based coding is very simple: It draws on the community’s most attractive, already-established designs, standardizes them for replication, and often conveys them through drawings rather than dense, unreadable text (see box, page 15). Rather than mandating what activities can occur within buildings, form-based coding describes the neighborhood’s or town center’s design, including walkways, parking, alleys, garages, front porches, street trees, architectural and building material standards, even the transparency of storefront windows.

The success of new town centers or neighborhoods depends on plenty of public input. Ultimately, designing a new town center or neighborhood depends on basics as simple as choosing designs that look nice and fit the community’s character. Residents should be listened to because they usually know the features that will create a place of lasting value and can quickly derail a project they dislike. Charrettes—intensely creative, multi-day planning sessions that include designers, architects, and local residents—are effective ways to design a project that has a practical, shared vision.

Element Three: Getting It Done

Once a design has the necessary approvals, the developer must coordinate financing and phasing.

Financing is challenging because of longer paybacks. Conventional developments typically seek maximum return within five to seven years, while mixed-use New Urbanist projects do not typically see significant returns for at least seven years. Building places that will last for generations costs more up front, but because they remain so desirable, their value continues to grow long after a suburban development’s value has peaked. So they are excellent long-term investments.

Traditional lenders often are less comfortable with such developments because they have such scant experience with them. However, that is changing as more developers work with New Urbanism; they often bring more of their own investment equity to a project to help finance their significant up-front design costs.

There are also some unique financing tools including tax increment financing, for streetscape improvements that enhance the project’s value; special assessment districts, often implemented by Downtown Development Authorities; state economic development funds; community development block grants; transportation planning funds; and affordable housing grants.

Timing is everything. How a developer “phases” different parts of a project is important to public perception and financial success. Building an anchor store early in a mixed-use project can generate traffic that helps sell additional retail spaces, and constructing a high-density neighborhood first can increase demand for nearby retail.

In the current regulatory and financing climate, it is more challenging to build a new town center or neighborhood than yet another ring of suburban tract housing. But New Urbanist builders, their municipal partners, and the people who live in those new developments know that the extra effort is worth it. As this trend arrives in northwest Michigan, it brings with it the promise of stronger communities, higher quality of life, lower taxes, and a more prosperous economy. It also offers a bright promise that can help sustain, rather than harm, the region’s rural beauty and charm.